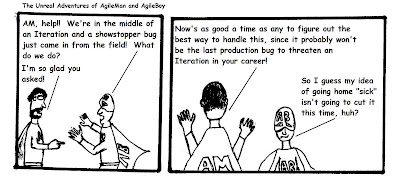

A friend of a friend (who actually follows this blog, I believe) e-mailed me yesterday, asking if I had any advice on how to handle a situation that his Agile team kept running into. Apparently they'd had several instances in the recent past where high priority production bugs had come to the team in the middle of a (Scrum) Sprint. In each case, it was considered unacceptable that the defect resolution simply wait for the next Sprint, and so they had tried a couple of different approaches to address the urgency of the situation:

A friend of a friend (who actually follows this blog, I believe) e-mailed me yesterday, asking if I had any advice on how to handle a situation that his Agile team kept running into. Apparently they'd had several instances in the recent past where high priority production bugs had come to the team in the middle of a (Scrum) Sprint. In each case, it was considered unacceptable that the defect resolution simply wait for the next Sprint, and so they had tried a couple of different approaches to address the urgency of the situation:- Include the bug-fixing activity in with another feature in that Sprint that was somewhat related

- Add the bug fix as a deliverable for the Sprint, with a higher priority than everything else

As I said in my e-mail response, both of those were reasonable ways with which to try to accommodate a difficult and frustrating scenario. However, I could easily imagine - even without knowing any of the people involved - how each might've gone awry. So instead I offered a different tack to consider next time, and it's the one that most Agile purists would likely always push for. But before I get to that, a few thoughts on the general topic of "bugs from the field."

Since I don't personally believe in "defect-free software" (having never produced, used or purchased any examples of such a mythical creature of legend second only to the unicorn), I go about my day under the strong assumption that there are always going to be problems found in production that weren't caught prior to getting there. Of those, some will be of a truly urgent nature that need immediate attention, and many won't be (but may still be initially prioritized as if they were); most almost certainly could have been detected and corrected before getting out the door had enough time and energy been expended in the search for them, and a few probably couldn't have been. In other words, they come in all shapes and sizes, but regardless: they come when they come! So, for me, the important question to be asked of any bug when it arrives back at our doorstep is, "What can we do better in the future to make production defects less likely." And if you're getting a significant enough quantity of showstopper bugs following release, then clearly you're not asking or (more importantly) answering that question adequately. Some serious and ongoing "inspect and adapt" discussions and tasks need to be happening if "stop the presses!" types of live bugs are more than an occasional occurrence for you and your team. That's one particular problem, and it's discreet from the one that was being posed of me.

What I was being asked was what to do in the short term, potentially high-pressure situation of dealing with the here-and-now of a bug's arrival and its effect on the current Iteration or Sprint. And, of course, the by-the-book answer is that you either cancel the Sprint and plan a new one to include the bug fix, or (somewhat less drastically) get the Product Owner to remove something from the Sprint in order to make room for the bug fix. I prefer the second approach because I'm not a big fan of bringing everything to a halt simply to accommodate something new. It may be that the bug in question is going to suck up so many of the resources for so long that you'll determine, while sizing it, that you're going to have to effectively cancel everything else anyway, but I'd prefer that an outcome like that simply remain an option, rather than the default response. In either case, though, you're taking actions that clearly send the message that fixing this bug is "not nothing." And that's critical because, among other things, it can sometimes result in the bug fix suddenly not being deemed as important as it had been when it had no price tag associated with it. It's like the free coffee and pop at my last workplace, which a few misguided souls there tended to treat rather disrespectfully (open can, take sip, leave remainder there for cleaning staff to deal with). When something's thought to be "free" that isn't really, it often gets some poor assumptions made about it.

Now, one argument against what I've just written that sometimes gets made goes like this: "Since the team didn't find the bug in the first place (but should have), then it's up to them to figure out how to fix it without jeopardizing everything else that they've committed to in the Iteration/Sprint." Honk if you've ever heard that one before! (Honk! Honk! Honk! Honk!)

There are a number of reasons why that's a silly stance to take, and I couldn't possibly think of them all in one sitting. But among the most obvious problems with it are:

- it encourages teams to fix things in the most slap-dash manner possible, since every minute they spend on the resolution is taking time away from what they were actually expecting (and expected) to work on

- it drives home the belief that the team is going to be penalized for every mistake they make, thereby making experimentation less likely (which is appropriate if you're programming a system for the Shuttle or a pacemaker, but in most cases...?)

- it flies fully in the face of the reality that even software organizations with tens of thousands of employees ship code with bugs

Getting back to the question of "how often does this happen?", I think that what I've outlined above works fine as long as the scenario we're talking about is the exception, and not the norm. However, if it's happening on a more frequent basis, then in addition to figuring out why (and doing something about it that should reduce the occurrences in the longer term) you may need to set aside a small percentage of the team's velocity every Iteration for critical bug fixes. As I said in my e-mail response, you really want to make sure that any time that's allocated for that use be limited to actually dealing with high priority bugs, or bringing work in (off the product backlog, in priority order) if no urgent defects come along by, say, the midway mark of the Iteration. It definitely should not become a "slush fund" that can be used to soften the blow related to under-estimating, get work in on pet projects or simply to provide a cushion for the team. (You may, of course, want to allow some Slack Time for the team to dream up process improvements or new tools, but that's a different discussion.) If you can do it right, the team will regard that extra time correctly, and no one outside the team will have any reason to resent it or try to eliminate it, because they'll see the value of it, either in terms of showstopper bugs being fixed quickly or additional features being delivered.

Of course, it's easy for me to offer advice when I'm not in the middle of the fray, but that's just the way the ball bounces at the moment. Maybe someday I'll be back in there, swinging for the fences...

2 comments:

Gene,

You're absolutely right, but I also believe that the process really depends on the stage your project is in.

If you're still working on the first release, then your initial approach might be more appropriate.

On the other hand, if v1 is production, and is now in the hands of a larger group of users, production bugs will be more frequent, so it's definitely a good idea to allocate a slice of the sprint to take care of them, while the rest of the budget is allocated to the backlog features that need to go into v2.

Another best practice that I like a lot is to include a special "Tuning Sprint" at the end of the project. This will ensure that when the application is deployed to a larger user base, we focus on getting it fine-tuned based on user feedback and bugs that have been found during real-life usage scenarios.

Michel

"Of course, it's easy for me to offer advice when I'm not in the middle of the fray"

Sometimes you need to be removed from a situation in order to see the obvious answer... it happens even to the best of us from time to time to forget the big picture of a situation when we're right in the middle of it.

Post a Comment